Long Live the C: Frequently Asked Questions

There are two issues – buffer overflow and integer overflow – in the following two functions. Can you identify the lines responsible for these problems?”

int authenticate() {

char input[8];

char password[8] = "liebe";

std::cout << "Enter password: ";

std::cin >> input;

if (std::strncmp(password, input, 8) == 0)

std::cout << "Access granted\n";

else

std::cout << "Access denied\n";

return 0;

}

int binary_search(int arr[], int size, int target) {

int left = 0;

int right = size - 1;

while (left <= right) {

int mid = (right + left) / 2;

if (arr[mid] == target)

return mid;

if (arr[mid] < target)

left = mid + 1;

else

right = mid - 1;

}

return -1;

}

Introduction

This page records all the C-related notes, frequently asked questions and prgramming assignments I’ve encountered over the years.

Variable-Length Array (VLA) in C and C++

Read https://zakuarbor.github.io/blog/variable-len-arr/

Array of Characters and String Literal

s1 is an array (not a pointer) of characters (character arrays) containing the

sequence “helloworld\0”. The size of s1 is determined by the number of characters in

the initializer, resulting in sizeof(s1) being 11 bytes. On the other hand, s2 is a

non-const pointer pointing to the first character of the constant string literals

“helloworld\0” which is stored in read-only memory in C. The size of s2 is 8 bytes on

a 64-bit system, representing the size of a pointer. s3 is an array of characters with

a specified size of 10 bytes. The initializer “helloworld” contains 10 characters plus

the null terminator ‘\0’, making it a total of 11 characters. Since s3 is declared

with a size of 10 bytes, it is not large enough to accommodate the null terminator,

resulting in a potential buffer overflow. This code might compile without any errors,

but it is a source of

undefined behavior.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

char s1[] = "Helloworld"; // s1 is an `array` with a length of 11 bytes.

char *s2 = "Helloworld"; // s2 is a non-const `pointer` pointing to a constant string literal.

char s3[10] = "helloworld";// DO NOT EVER DO THIS. s3 is an `array` with a length of 10 bytes.

printf("s1: %s. sizeof(s1): %ld\n", s1, sizeof(s1));

printf("s2: %s. sizeof(s2): %ld\n", s2, sizeof(s2));

printf("s3: %s. sizeof(s3): %ld\n", s3, sizeof(s3));

printf("The 1st character of s1 is %c %c\n", *s1, s1[0]);

printf("The 1st character of s2 is %c %c\n", *s2, s2[0]);

printf("The 1st character of s3 is %c %c\n", *s3, s3[0]);

printf("The 11th character of s1 is %c %d\n", *(s1+10), s1[10]);

printf("The 11th character of s2 is %c %d\n", *(s2+10), s2[10]);

printf("The 11th character of s3 is %c %d\n", *(s3+10), s3[10]);

printf("\nModify s1 ...\n");

s1[0] = 'h'; // Modifying the 1st character from 'H' to 'h'.

printf("s1: %s. sizeof(s1): %ld\n", s1, sizeof(s1));

printf("\nModify s3 ...\n");

s3[0] = 'H'; // Modifying the 1st character from 'h' to 'H'.

printf("s3: %s. sizeof(s3): %ld\n", s3, sizeof(s3));

printf("\nModify s2 ...\n");

s2[0] = 'H'; // Attempting to change the 1st character leads to a segmentation fault.

printf("s2: %s. sizeof(s2): %ld\n", s2, sizeof(s2));

}

The output is the following:

s1: Helloworld. sizeof(s1): 11

s2: Helloworld. sizeof(s2): 8

s3: helloworldHelloworld. sizeof(s3): 10

The 1st character of s1 is H H

The 1st character of s2 is H H

The 1st character of s3 is h h

The 11th character of s1 is 0

The 11th character of s2 is 0

The 11th character of s3 is H 72

Modify s1 ...

s1: helloworld. sizeof(s1): 11

Modify s3 ...

s3: Helloworldhelloworld. sizeof(s3): 10

Modify s2 ...

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

There are few things to notice:

-

Printing characters from

s1,s2ands3is done similarly. Both*and[]can be used to access elements in C-strings and arrays. However, it’s crucial to recognize thats1ands2are fundamentally two different entities. -

The size of the array

s3is specified as 10 bytes, but the string “helloworld” requires 11 bytes (10 characters + null terminator \0). This will result in a buffer overflow, causing undefined behavior and potentially leading to unexpected issues in your program. Don’t ever do it. -

Attempting to modify the contents of

s1is permissible becauses1is an array, and arrays in C are mutable. In contrast, attempting to modifys2leads to a segmentation fault. This is becauses2points to a read-only constant string literal, and modifying such literals in C results in a runtime error.

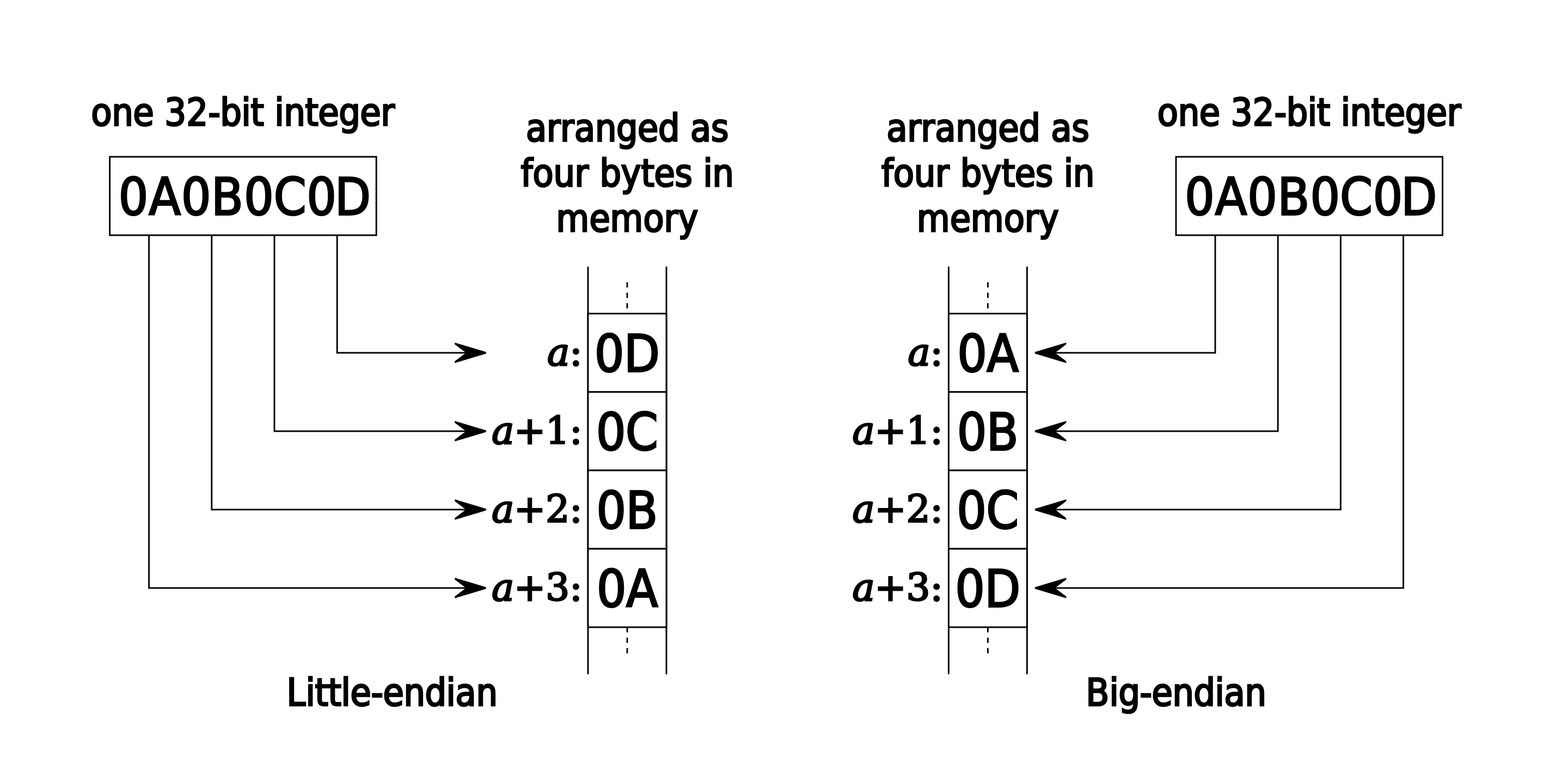

How to tell if a system is little-endian or big-endian?

A big-endian system stores the most-significant byte (MSB) of a word at the smallest

memory address and the least-significant byte (LSB) at the largest. A little-endian

system, in contrast, stores the least-significant byte at the smallest address. Also,

consider an integer int n = 0x0A0B0C0D;. In this case, 0A represents the MSB, while

0D is the LSB. The significance here refers to the influence a byte has on the value

of the integer. Changes to the most significant byte have a more significant impact on

the integer’s value than changes to the least significant byte.

To better understand endianness, let’s take a look at this visual representation:

Endian example.

Endian example.

The endianness of a system can be determined using C code. The following code snippet prints the byte values of an integer from the smallest memory address to the highest address:

int main(void) {

int n = 0x0A0B0C0D;

printf("Hexadecimal: 0x%08X\n", n);

for (int i = 0; i < sizeof(n); ++i) {

printf("%p: %X\n", (void *)(char *)&n + i, *((char *)&n + i));

}

}

In the code snippet, the expression (char *)&n + i is used to access individual bytes

of an integer n. The (char *)&n part treats the address of n as a pointer to a

character (byte), and then + i is used to access each byte one by one within a loop.

Hexadecimal: 0x0A0B0C0D

0x7ffe4e964310: D

0x7ffe4e964311: C

0x7ffe4e964312: B

0x7ffe4e964313: A

It shows the least significant byte 0D occupies the smallest address and the most

significant byte 0A occupies the biggest. Thus, my system is a little-endian system.

Convert a string representation of a signed integer into an integer.

The function below converts a string representation of a signed integer into an integer while also addressing concerns related to integer overflow.

#define MAXIMUM 127

#define MINIMUM -128

int str2int(const char *s, int *result) {

assert(MAXIMUM / 10 == 12);

assert(MAXIMUM % 10 == 7);

assert(MINIMUM / 10 == -12);

assert(MINIMUM % 10 == -8);

while (*s == ' ' || *s == '\t') {

s++; // Skip leading white spaces

}

int sign = 0;

if (*s == '-') {

sign = -1;

s += 1;

} else {

sign = 1;

}

int num = 0;

while (*s != '\0') {

if (*s >= '0' && *s <= '9') {

int digit = (*s - '0');

// It cannot check integer overflow after operation because it's too late.

if (sign == 1) {

if (num > MAXIMUM / 10 ||

(num == MAXIMUM / 10 && digit > MAXIMUM % 10)) {

return -1;

}

} else {

if (-num < MINIMUM / 10 ||

(-num == MINIMUM / 10 && -digit < (MINIMUM % 10))) {

return -1;

}

}

num = 10 * num + digit;

s += 1;

} else {

return -2; // Non-digit character encountered

}

}

*result = sign * num;

return 0;

}

Write a generic function to swap strings and arrays.

Implement a swap function such that the following code

int main() {

char *h = "hell";

char *w = "world";

printf("%s %s\n", h, w);

// swap(h, w)

printf("%s %s\n", h, w);

char c[5] = { 'a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u' };

char d[3] = { '1', '2', '3' };

print_array(c, 5);

print_array(d, 3);

// swap(c, d)

print_array(c, 3);

print_array(d, 5);

return 0;

}

generates the output

hell world

world hell

a e i o u

1 2 3

1 2 3

a e i o u

First, this task is impossible given

the above example code, because the

array c and d don’t have the same size. Second, h and w are two pointers (a

pointer is a variable that contains the address of a variable.) while c and d are

two arrays. Pointers and arrays are not the same thing. Third, designing a generic

swap function to swap objects of any type is doable, but for the swap to be possible,

the objects must have the same size. Here is the correct implementation:

#include <stddef.h>

#include <stdio.h>

void swap_memory(void *a, void *b, size_t n) {

char *pa = a;

char *pb = b;

char *end_pa = pa + n;

while (pa != end_pa) {

char tmp = *pa;

*pa = *pb;

*pb = tmp;

pa++;

pb++;

}

}

void print_array(const char *c, size_t size) {

for (size_t i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

printf("%c ", c[i]);

}

printf("\n");

}

int main() {

// NOTE: `h` is a pointer to a constant character. It means that I can't use `h` to

// modify the characters in the string it points to, but I can reassign `h` to point

// to a different string. Now, what does `const char *const h = "hell";` mean?

const char *h = "hell";

const char *w = "world"; // NOTE: "hell" and "world" do not have the same length.

printf("%s %s\n", h, w);

swap_memory(&h, &w, sizeof(char *)); // NOTE: 32-bit or 64-bit

printf("%s %s\n", h, w);

char c[5] = { 'a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u' };

char d[5] = { '1', '2', '3' };

print_array(c, 5);

print_array(d, 3);

swap_memory(c, d, 5); // or `(&c, &d, 5)`, doesn't matter.

print_array(c, 3);

print_array(d, 5);

return 0;

}

Create a function to print every elements in a 2D array.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void print_2d_array_subscript(int rows, int cols, int arr[rows][cols]);

void print_2d_array_offset(int *arr, int rows, int cols);

void print_2d_array_subscript(int rows, int cols, int arr[rows][cols]) {

for (int i = 0; i < rows; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < cols; j++) {

printf("%d ", arr[i][j]);

}

printf("\n");

}

}

void print_2d_array_offset(int *arr, int rows, int cols) {

for (int i = 0; i < rows; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < cols; j++) {

printf("%d ", *(arr + i*cols + j));

}

printf("\n");

}

}

int main () {

int arr[2][5] = {

{1, 2, 3, 4, 5},

{6, 7, 8, 9, 10}

};

print_2d_array_offset(&arr[0][0], 2, 5);

print_2d_array_subscript(2, 5, arr);

return 0;

}

Explain padding and alignment in C.

#include <stdio.h>

typedef struct _engineer {

char *title;

int age; // 4 bytes

long salary; // 8 bytes

} Engineer;

typedef struct _designer {

char *title;

int age; // 4 bytes

long salary; // 8 bytes

} __attribute__((packed)) Designer;

typedef struct _manager {

char *title;

short age; // 2 Bytes

int salary; // 4 bytes

} Manager;

#pragma pack(push, 1)

typedef struct _sale {

char *title;

short age; // 2 Bytes

int salary; // 4 bytes

} Sale;

#pragma pack(pop)

int main () {

Engineer e;

Designer d;

Manager m;

Sale s;

printf("Size of Engineer is %lu. e.title: %p. e.age: %p. e.salary: %p\n", sizeof(e), &e.title, &e.age, &e.salary);

printf("Size of Designer is %lu. d.title: %p. d.age: %p. d.salary: %p\n", sizeof(d), &d.title, &d.age, &d.salary);

printf("Size of Manager is %lu. m.title: %p. m.age: %p. m.salary: %p\n", sizeof(m), &m.title, &m.age, &m.salary);

printf("Size of Sale is %lu. s.title: %p. s.age: %p. s.salary: %p\n", sizeof(s), &s.title, &s.age, &s.salary);

return 0;

}

shows the following output:

Size of Engineer is 24. e.title: 0x7fffb0d4b660. e.age: 0x7fffb0d4b668. e.salary: 0x7fffb0d4b670

Size of Designer is 20. d.title: 0x7fffb0d4b640. d.age: 0x7fffb0d4b648. d.salary: 0x7fffb0d4b64c

Size of Manager is 16. m.title: 0x7fffb0d4b630. m.age: 0x7fffb0d4b638. m.salary: 0x7fffb0d4b63c

Size of Sale is 14. s.title: 0x7fffb0d4b622. s.age: 0x7fffb0d4b62a. s.salary: 0x7fffb0d4b62c

The observed differences in structure sizes are due to structure padding and alignment in C. Typically, structures are padded to align their members with the largest member’s size (in byte). In all four cases, the biggest members are all 8 bytes (char *). Thus all elements will be padded according 8 bytes.

EngineerStructure: To ensure salary is aligned on 8 bytes, 4 bytes of padding are added afterage.DesignerStructure: Thepackedattribute ensures that there is no padding between structure members, potentially reducing the overall size of the structure in memory. However, note that using this attribute may result in slower access times for structure members due to the lack of alignment.ManagerStructure: 2 bytes of padding are added afterageso that the combined size ofageandsalaryaligns on 8 bytes.SaleStructure: Padding is explicitly disabled within its scope using#pragma pack(1).

Create 1-Diemensional Array of pointers.

int* arr[5];

printf("`arr` is an array with five pointers, and each pointer points to an interger. The address of `arr` is %p.\n", arr);

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

*(arr+i) = (int *) malloc(sizeof(int));

**(arr+i) = i;

}

printf("`arr+2` means the address of the 2-th (0-based, so it's actually the third) element in arr is %p.\n", arr+2);

printf("`*(arr+2)` means that the 2-th element, which is a pointer, points to an address %p.\n",*(arr+2));

printf("`**(arr+2)` means the integer which the 2-th pointer points to is %d.\n", **(arr+2));

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

free(*(arr+i));

}

The output is shown below and it’s pretty standard. Please explain why there is a

difference of 16 between arr+2 and arr.

`arr` is an array with five pointers, and each pointer points to an interger. The address of `arr` is 0x7ffe971ed070.

`arr+2` means the address of the 2-th (0-based, so it's actually the third) element in arr is 0x7ffe971ed080.

`*(arr+2)` means that the 2-th element, which is a pointer, points to an address 0x55ace4c866f0.

`**(arr+2)` means the integer which the 2-th pointer points to is 2.

Explain memory layout of a process.

Here is the demonstration code.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int uninit_global;

int init_global = 1000;

void allocate_memory(int **arr, int size, int value)

{

int uninit_local1 = 302;

int init_arr[3] = {0, 1, 2};

int uninit_local2;

printf("<allocate_memory>:\n");

printf("%p: init_arr\n", &init_arr);

printf("%p: uninit_local2\n", &uninit_local2);

printf("%p: uninit_local1\n", &uninit_local1);

printf("%p: address of parameter `arr`\n", &arr);

printf("%p: address of parameter `size`\n", &size);

printf("%p: address of parameter `value`\n", &value);

printf("\ncalling `malloc()` to allocate memory to `arr`\n");

printf("\n===== End of Stack =====\n\n");

printf("{Stack and Heap are growing toward each other.}\n\n");

printf("===== End of Heap =====\n\n");

*arr = (int *) malloc(size * sizeof(int));

printf("%p: returned address of `malloc()`.\n", *arr);

printf("\n");

printf("===== Start of Heap =====\n");

}

int main () {

int uninit_local1;

int init_local = 302;

int uninit_local2;

static int static_init_local = 2380;

static int static_uninit_local;

printf("Here is the memory layout of a process\n\n");

printf("===== Start of Stack =====\n\n");

printf("<main>:\n");

int later_defined = 10;

int *later_defined_ptr = NULL;

printf("%p: later_defined_ptr's address\n", &later_defined_ptr);

printf("%p: later_defined's address\n", &later_defined);

printf("%p: uninitialized local variable 2\n", &uninit_local2);

printf("%p: initialized local variable\n", &init_local);

printf("%p: uninitialized local variable 1\n", &uninit_local1);

printf("\nCalling `allocate_memory()` function.\n");

allocate_memory(&later_defined_ptr, 5, 45);

printf("\n===== End of Uninitialized Data (global and static) (bss) =====\n\n");

printf("%p: uninitialized global variable\n", &uninit_global);

printf("%p: static uninitialized local variable\n", &static_uninit_local);

printf("\n===== Start of Uninitialized Data (bss) =====\n");

printf("\n===== End of Initialized Data =====\n\n");

printf("%p: static initialized local variable\n", &static_init_local);

printf("%p: initialized global variable\n", &init_global);

printf("\n===== Start of Initialized Data =====\n");

return 0;

}

The output message is shown below. Please explain why it looks like this.

===== Start of Stack =====

<main>:

0x7ffec5a9cf70: later_defined_ptr's address

0x7ffec5a9cf6c: later_defined's address

0x7ffec5a9cf68: uninitialized local variable 2

0x7ffec5a9cf64: initialized local variable

0x7ffec5a9cf60: uninitialized local variable 1

Calling `allocate_memory()` function.

<allocate_memory>:

0x7ffec5a9cf2c: init_arr

0x7ffec5a9cf28: uninit_local2

0x7ffec5a9cf24: uninit_local1

0x7ffec5a9cf18: address of parameter `arr`

0x7ffec5a9cf14: address of parameter `size`

0x7ffec5a9cf10: address of parameter `value`

calling `malloc()` to allocate memory to `arr`

===== End of Stack =====

{Stack and Heap are growing toward each other.}

===== End of Heap =====

0x5626a7c046b0: returned address of `malloc()`.

===== Start of Heap =====

===== End of Uninitialized Data (global and static) (bss) =====

0x5626a6956020: uninitialized global variable

0x5626a695601c: static uninitialized local variable

===== Start of Uninitialized Data (bss) =====

===== End of Initialized Data =====

0x5626a6956014: static initialized local variable

0x5626a6956010: initialized global variable

===== Start of Initialized Data =====

How to reverse byte orders from 0x12345678 to 0x78563412?

- Use

memcpy:

#include <stdint.h> // uint32_t, uint8_t

#include <stdio.h> // printf

#include <stdlib.h> // malloc

#include <string.h> // memecpy

void reverse_byte_order(void *data, uint32_t num_bytes) {

// malloc(num_bytes). calloc(num_elements, sizeof(element))

// num_bytes = num_elements * sizeof(element)

void *dest = malloc(num_bytes);

for (int i = 0; i < num_bytes; ++i) {

memcpy(dest + num_bytes - i - 1, data + i, 1);

}

memcpy(data, dest, num_bytes);

free(dest);

}

int main() {

uint32_t data1 = 0x12345678;

printf("0x%08x\n", data1);

reverse_byte_order(&data1, 4);

printf("0x%08x\n", data1);

uint32_t data2 = 0xabcdef;

printf("0x%08x\n", data2);

reverse_byte_order(&data2, 3);

printf("0x%08x\n", data2);

return 0;

}

- Without using additional memory:

void reverse_byte_order(void *data, uint32_t num_bytes) {

uint8_t *start = data;

uint8_t *end = data + num_bytes - 1;

while (start < end) {

// Swap the bytes pointed to by 'start' and 'end'.

uint8_t temp = *start;

*start = *end;

*end = temp;

// Move the pointers toward each other.

start++;

end--;

}

}

What’s the difference between i++ and ++i?

i++ is known as post increment whereas ++i is called pre increment. ++i will

increment the value of i, and then return the incremented value. i++ will increment

the value of i, but return the original value that i held before being incremented.

E.g., The following C snippet

int j = 1, k = 0;

j = k++;

printf("j = %d, k = %d\n", j ,k);

j = ++k;

printf("j = %d, k = %d\n", j ,k);

creates the output below.

j = 0, k = 1

j = 2, k = 2

Let’s look at some assembly code to verify that.

// test.c

#include <stdio.h>

void foo() {

int a, b;

a = 1;

// use one of these five at a time

// b = a++;

// b = ++a;

// b = (a += 1);

// b = (a = a + 1);

// b = a++ + ++a;

}

int main() {

foo();

return 0;

}

One thing to keep in mind is that when a stack frame is created , it’s growing toward

lower memory address. And it’s guaranteed that &b > &a. So in our example, the

address rbp-0x4 points to the variable b while rbp-0x8 points to a. Thus, the

assignment a = 1; is always translated to mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],0x1. Now we are

ready to dive into the assembly.

-

In the case of

b = a++;, it has the following assembly code$ gcc test.c && objdump -M intel -D a.out | grep -A10 foo.: 0000000000001129 <foo>: 112d: 55 push rbp 112e: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp 1131: c7 45 f8 01 00 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],0x1 1138: 8b 45 f8 mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8] 113b: 8d 50 01 lea edx,[rax+0x1] 113e: 89 55 f8 mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],edx 1141: 89 45 fc mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4],eax 1144: 90 nop-

First,

a++is associated tomov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8] lea edx,[rax+0x1]which first moves the value of

aintoeaxand then computesa+1and moves the result intoedx. - Second, it moves the value of

edxintoa. - Last, it moves the value of

eaxintob. Thus,a == 1andb == 0beforefooreturns.

-

-

In the case of

b = ++a;,b = (a += 1);, andb = (a += 1);, they have the following assembly code$ gcc test.c && objdump -M intel -D a.out | grep -A10 foo.: 0000000000001129 <foo>: 112d: 55 push rbp 112e: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp 1131: c7 45 f8 01 00 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],0x1 1138: 83 45 f8 01 add DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],0x1 113c: 8b 45 f8 mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8] 113f: 89 45 fc mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4],eax 1142: 90 nop-

First,

++ais associated toadd DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],0x1 mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8]which first adds

awith 1 and movesaintoeax. -

Second, it moves the value of

eaxintob. Thus,a == 1andb == 1beforefooreturns. As you can see, the assembly code is one line fewer than the previous case. I reckon that’s why people are talking about using++iis more efficient in general.

-

-

Finally, in the case of

b = a++ + ++a;, its assembly code is$ gcc test.c && objdump -M intel -D a.out | grep -A12 foo.: 0000000000001129 <foo>: 112d: 55 push rbp 112e: 48 89 e5 mov rbp,rsp 1131: c7 45 f8 01 00 00 00 mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],0x1 1138: 8b 45 f8 mov eax,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8] 113b: 8d 50 01 lea edx,[rax+0x1] 113e: 89 55 f8 mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],edx 1141: 83 45 f8 01 add DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8],0x1 1145: 8b 55 f8 mov edx,DWORD PTR [rbp-0x8] 1148: 01 d0 add eax,edx 114a: 89 45 fc mov DWORD PTR [rbp-0x4],eax 114d: 90 nopwhich can be broken down as follow:

ais first moved intoeax(Ln. 1138), added with 1 and stored inedx.edxis moved toa(Ln. 113e), and it adds 1 toa(Ln. 1141).- Next,

ais moved intoedx. and addedxtoeax. - Lastly,

eaxis moved tob. Thus,a == 3andb == 4beforefooreturns. To be honest, without looking into assembly code, I am not able to answer this question. Thus, please DO NOT write code like this. An “intuitive” way to think about this is the followb = a++ + ++a; --> 1 + (1+1) --> a = 3 = 2+1 --> b = 1 + 3Still, it’s counter intuitive.